The Artist Is Always In

MY ROLE:

User Researcher

TEAM:

Nathan Barnhart, Stacy Kellner, Amanda Yang

WHEN:

October 2019 - December 2019

TOOLS & METHODS:

User Researcher

TEAM:

Nathan Barnhart, Stacy Kellner, Amanda Yang

WHEN:

October 2019 - December 2019

TOOLS & METHODS:

- Affinity Diagrams

- Observe & Intercept

- Think-Alouds

- Storyboarding & Speed Dating

- Experience Prototyping

Most citizens have little interest in the process of developing and implementing public art.

This UX research project explores the question: “how might we get citizens more involved?”. We quickly learned that most don't care about being involved in the first place

and at first glance, this looked like a dead end. But then we asked one more “why,” and realized that lack of interest

had to do with a key need being unfulfilled - citizens needed a convenient way to learn more.

Our solution is an interactive audio installment at the site of the public art, which presents the project's key facts and figures, while giving viewers the chance to learn more about the placement of public art. This educational tool helps Pittsburgh residents engage more deeply with their public spaces, and may open the door to stronger participation in future public art decisions.

Our solution is an interactive audio installment at the site of the public art, which presents the project's key facts and figures, while giving viewers the chance to learn more about the placement of public art. This educational tool helps Pittsburgh residents engage more deeply with their public spaces, and may open the door to stronger participation in future public art decisions.

The Problem

The overarching goal of our research was to identify the means in which we could help citizens be more involved in the public art process - by process, this could mean having a say in what public art work gets installed in a neighborhood, or having a part in the maintenance and creation process.

However, we found that many people do not have any interest in being involved in the public art process. Our research focuses on trying to identify: (a) the reasons for this lack of interest, and (b) a potential solution to help bolster this interest.

Methods and the Research Process

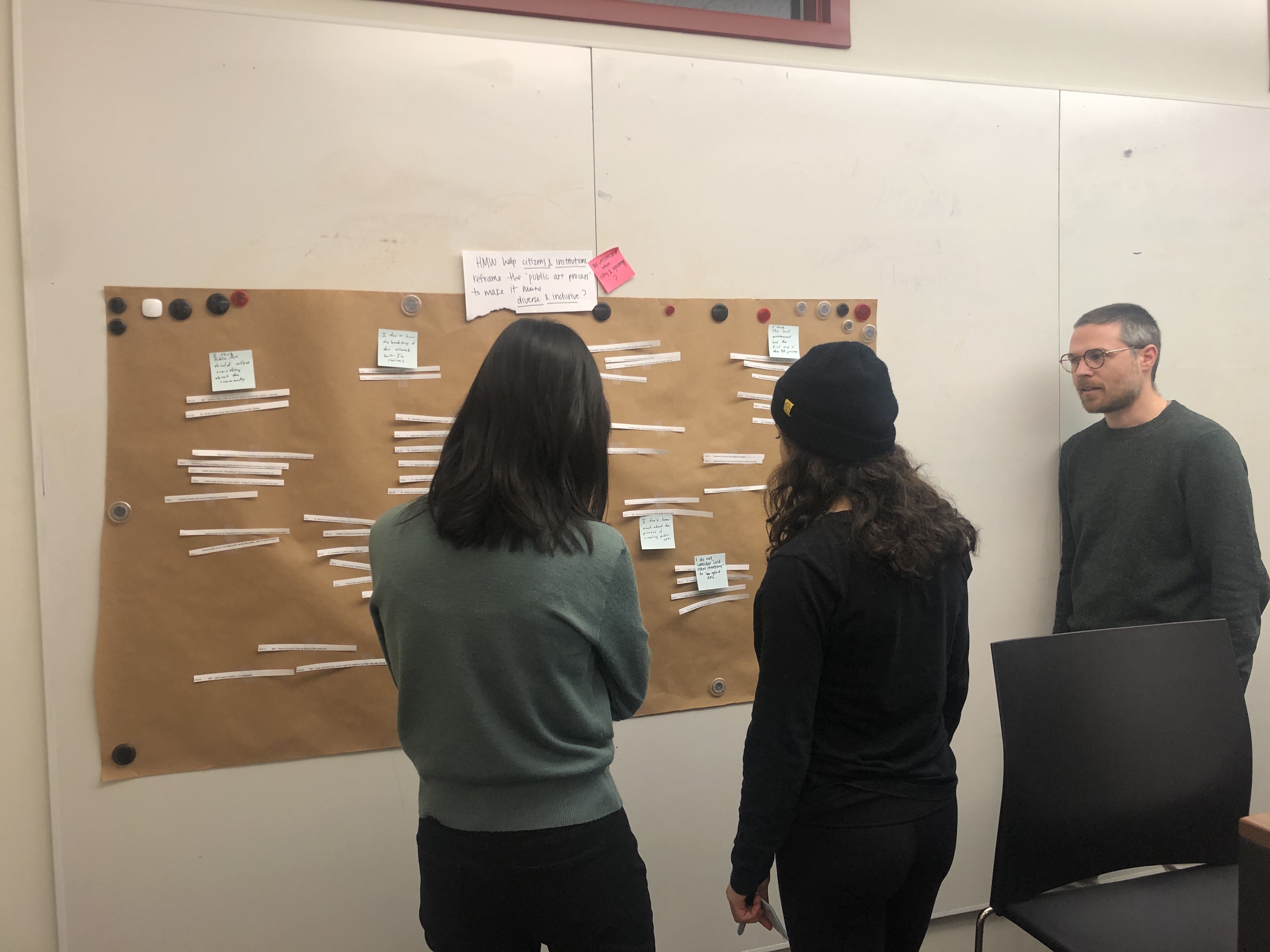

Late October 2019

Observe & Intercept, Affinity Diagramming

We conducted intercepts primarily around the Agnes R. Katz Plaza in downtown Pittsburgh

in order to gain a general understanding of our problem space, and to gauge citizens' interest

with public art or its process.

Our intercepts focused on asking questions to do with:

After conducting these intercepts on individuals, we derived the following insights understanding affinity diagramming:

Our intercepts focused on asking questions to do with:

- (a) individual personal definitions of public art,

- (b) whether public art is a way for a community to express itself,

- (c) individual awareness of the process of implementing public art projects, and

- (d) interest level in involvement with public art projects.

After conducting these intercepts on individuals, we derived the following insights understanding affinity diagramming:

- - People have a minimal interest in the public art process,

- - Citizens’ engagement in the art selection process comes mostly in the form of negative feedback, and

- - Citizens want to have a say in the process, but find current methods inconvenient (e.g. town hall meetings).

Early November 2019

Think-Alouds

We now wanted to explore potential reasons for this minimal interest - do citizens feel that their voices are

not heard? Do they not trust that the city will act on requests that they might have?

To investigate currently-existing applications that served to promote user engagement in city processes, we investigated the MyBurgh mobile app, which allows users to submit a service request for anything city-related. We conducted a series of TAP studies, primarily to identify what particular needs users had with regards to knowing that their voice was heard by the city, or how much they trusted the city to follow through with any sort of request in the first place.

The general insight that we found from these studies was that people do have a lot to say when it is something they care about, but felt that there needed to be improved two-way communication between the city and its citizens.

To investigate currently-existing applications that served to promote user engagement in city processes, we investigated the MyBurgh mobile app, which allows users to submit a service request for anything city-related. We conducted a series of TAP studies, primarily to identify what particular needs users had with regards to knowing that their voice was heard by the city, or how much they trusted the city to follow through with any sort of request in the first place.

The general insight that we found from these studies was that people do have a lot to say when it is something they care about, but felt that there needed to be improved two-way communication between the city and its citizens.

Mid November 2019

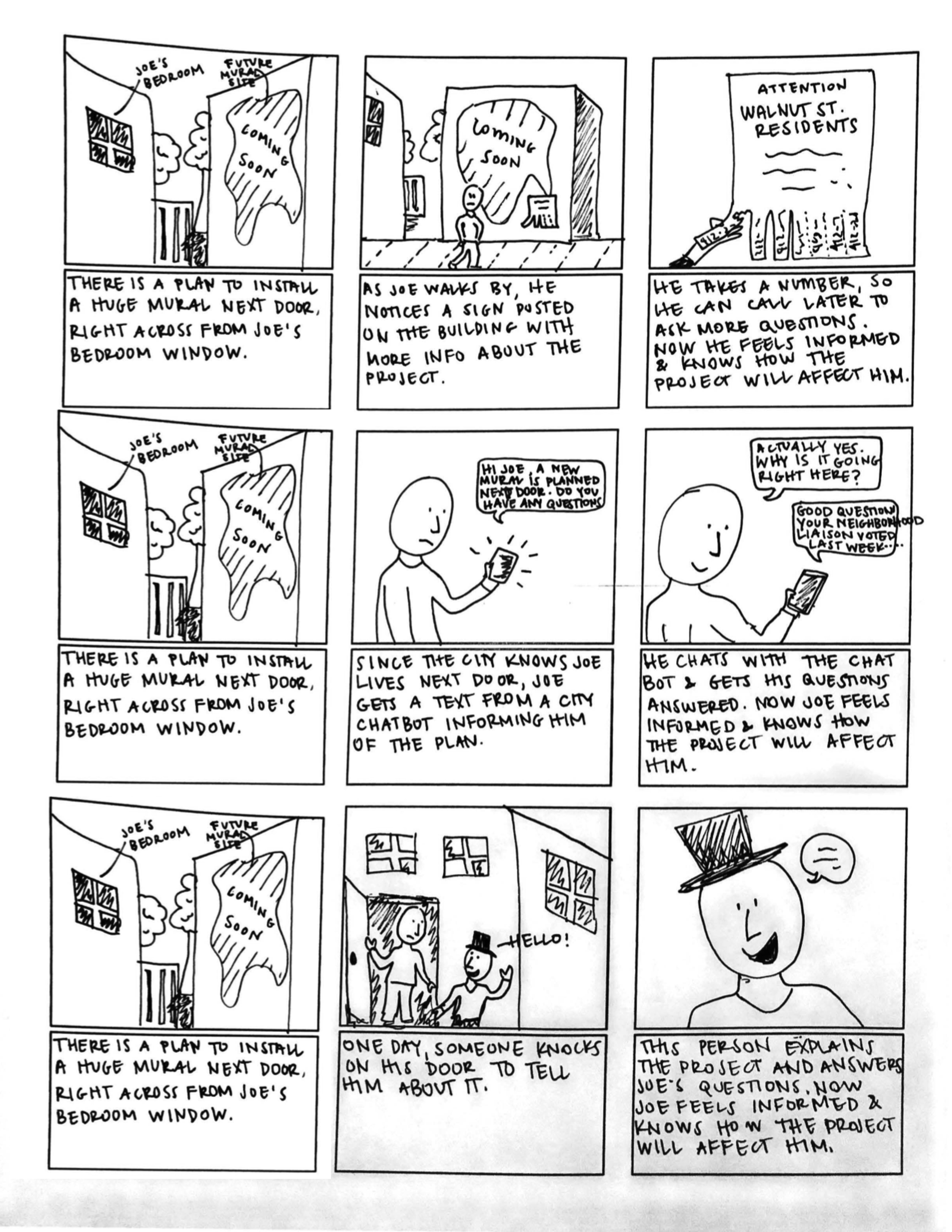

Storyboarding, Speed Dating

We then entered a phase of need validation. From out previous studies, we derived

a series of needs that citizens potentially have, and could be the unmet needs

that prevent citizens from wanting to be engaged with the public art process.

We created a series of storyboards, each representing a different need. The needs we wanted to validate were:

We found that through speed dating each of our storyboards, our first, third and fourth needs were validated, and that people additionally placed great value in human-interaction - whether this be to do with learning about public art opportunity involvement, or about the potential art works themselves. The need to have a convenient way to be involved was also validated across multiple participants, and hinted to us that this may be the reason why individuals did not feel compelled to be involved in the public art process - why would they want to be involved in a process that they knew nothing about?

We created a series of storyboards, each representing a different need. The needs we wanted to validate were:

- 1) Citizens need a more convenient way to be involved in the public art process.

- 2) Citizens would like to know their opinions about public art are valued.

- 3) Even if they generally are not very interested in public art, citizens want to know when something will impact them directly.

- 4) People need information about upcoming public art projects to be convenient.

We found that through speed dating each of our storyboards, our first, third and fourth needs were validated, and that people additionally placed great value in human-interaction - whether this be to do with learning about public art opportunity involvement, or about the potential art works themselves. The need to have a convenient way to be involved was also validated across multiple participants, and hinted to us that this may be the reason why individuals did not feel compelled to be involved in the public art process - why would they want to be involved in a process that they knew nothing about?

Main Insights & Evidence

After the bulk of our research was completed, we derived a series of core insights identified throughout the entire process.

These insights would then go on to fuel our solution.

"I have never thought about how [this artwork] got here."

Citizens will not want to be involved in a process they know nothing about. Before asking them to help select future art pieces, they should be told how the current ones came to be.

"I want to go to the meetings but they always happen at a bad time."

At present, being informed is a hassle. Town hall meetings conflict with busy schedules; advertisements are few and far between. Information should be presented openly and in a digestible way.

"I value face-to-face interaction."

In learning about public art, users preferred in-person conversations, not digital interfaces. These two-way dialogues made users feel their voices were being heard.

"Often when you go to community meetings, you get a lot of older, retired people."

Retired couples have an easier time going to town hall meetings; teenagers are fluent in social media. An individual’s preferences may even vary day-to-day; a good solution should allow for various forms of engagement.

Interest is fueled by information.

"I have never thought about how [this artwork] got here."

Citizens will not want to be involved in a process they know nothing about. Before asking them to help select future art pieces, they should be told how the current ones came to be.

Convenience is key.

"I want to go to the meetings but they always happen at a bad time."

At present, being informed is a hassle. Town hall meetings conflict with busy schedules; advertisements are few and far between. Information should be presented openly and in a digestible way.

Human interaction matters.

"I value face-to-face interaction."

In learning about public art, users preferred in-person conversations, not digital interfaces. These two-way dialogues made users feel their voices were being heard.

Engagement is not one-size-fits-all.

"Often when you go to community meetings, you get a lot of older, retired people."

Retired couples have an easier time going to town hall meetings; teenagers are fluent in social media. An individual’s preferences may even vary day-to-day; a good solution should allow for various forms of engagement.

The Solution

In response to our overarching insights, we understood that in order to promote citizen's interest in the public art process,

they would need to learn about the process first, and the means by which one would learn about this process had to be

convenient and promote human interaction as much as possible.

Our solution is an on-site display, in which the user can press a series of buttons to hear audio recordings that detail the process and origins of a particular art piece. We opted to have someone tell this information (via audio recordings) as it served to be a good proxy for in-human interaction, and we hoped that this form of information transfer would be much more engaging than reading about the process on a plaque.

Our solution is an on-site display, in which the user can press a series of buttons to hear audio recordings that detail the process and origins of a particular art piece. We opted to have someone tell this information (via audio recordings) as it served to be a good proxy for in-human interaction, and we hoped that this form of information transfer would be much more engaging than reading about the process on a plaque.

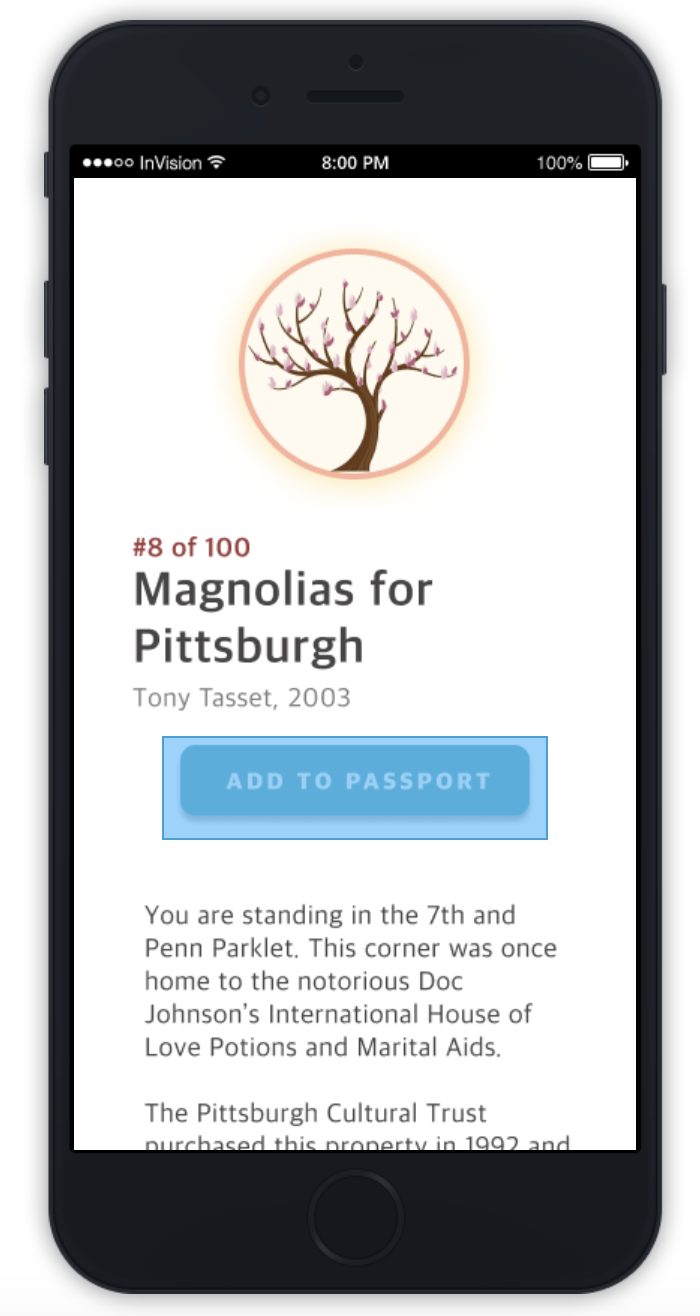

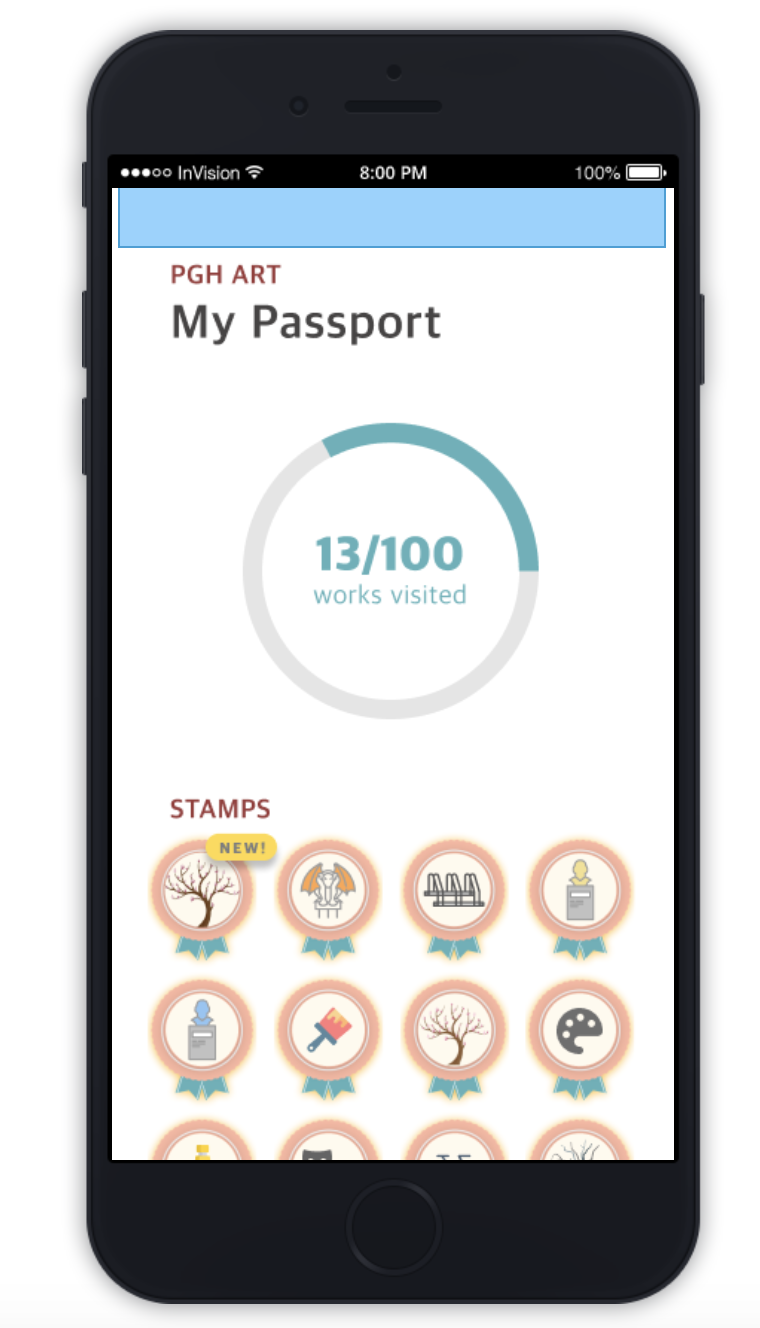

We additionally wanted to employ a gamification aspect, particularly to attract the younger generation (as observed from

our fourth insight, not all engagement is one-size-fits-all). We used the concept of badge collecting, in which users

would scan the QR code on the display, which would earn them a digital badge for having visited the artwork.

The application would also display all the other badges yet to be collected, and hopefully would serve as a motivator

to continue to explore more art pieces.

Here is the [link] to the InVision prototype.

Here is the [link] to the InVision prototype.

Conclusions

We brought our prototype out into the field, and found that citizens greatly enjoyed interacting with our display. Additionally, we found that once someone stopped to listen to a recording, passer-bys would also stop, as they were curious as to what the display was doing. So in the end, the benefits were two-fold: our prototype not only provided an opportunity to engage and learn about the public art process, but additionally drew the attention of other users, who otherwise may not have stopped to look at the artwork.

Overall, the entire project was a great learning experience, and really showed that citizens will demonstrate interest towards the public art process if they are given convenient opportunities to do so. This holds great opportunity in getting citizens involved in public art decisions, especially now that they are more familiar with the public art process itself.

.jpg)